Leica M9 (and M Lens) Reviews, Tests, Comparisons

Leica M9 (and M Lens) Reviews, Tests and Comparisons

Using rangefinder lenses on a full frame camera with no anti alias filter!

Jeffrey R. Charles.

Copyright 2012-2017, 2019, 2021, 2025 Jeffrey R. Charles All Rights Reserved.

(Lens Review, Comparisons, etc., Chapters Only:)

Copyright 1975, 1997, 2004-2017, 2019, 2021, 2023, 2025 Jeffrey R. Charles, All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.versacorp.com/vlink/jcreview/leicam9r.htm

Leica M9 with 35mm f/2 Summicron-M Asph Lens

|

Contents:

- 1.) Introduction and Conventions

- 2.) Leica M9: A Compact and Portable Camera System

- 3.) Compatibility with Vintage Compact Leica System Cases

- 4.) Initial Results with the Leica M9 (Almost no radial blur!)

- 5.) Moire, Green Stripes, Hot Pixels, Other Artifacts, and Sensor Corrosion

- 6.) Everyday Pictures with the Leica M9

- 7.) Astrophotography with the Leica M9, Plus a Simple IR Cut Filter Test

- 8.) Lens Coding. It works great!

- 9.) Using Various Accessories with the Leica M9

- 10.) Conclusions

- Appendix A: Leica M9 Apparently Fails to Reach Infinity Focus w/any of 13 Lenses (2013)

- Appendix B: Results After 2014 Leica M9 Warranty Repair (See Ap. B2 for 2015 Repair)

- Ap. B1: Rangefinder Came Back Misaligned. (See Ap. B2 for W. Repair Results)

- Ap. B2: Infinity, Rangefinder, Sensor Performance after early 2015 Warranty Service (2015)

- Ap. B3: Infinity, Rangefinder, Sensor Performance after CCD Sensor Replacement (2017)

- Appendix C: Comparing Leica M9 Camera to Hasselblad-Imacon V96C Digital Back (2013)

- Appendix D: Performance of Leica Mount Lenses Used/Tested to Date (Cumulative Results)

- Appendix E: Comparison of Various 35mm and 40mm Lenses (2013)

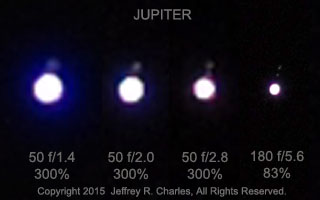

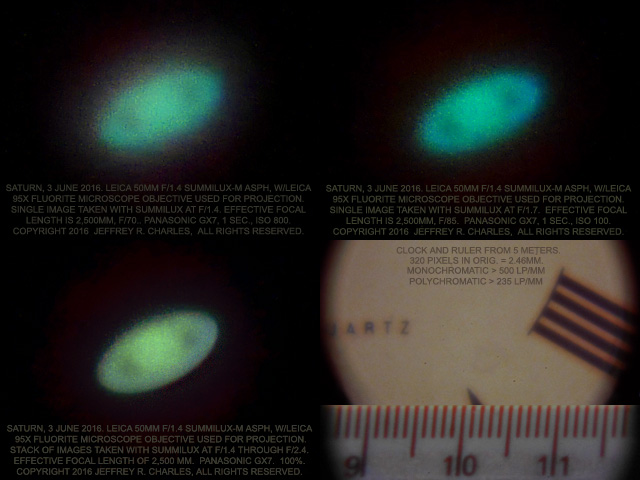

- Appendix F: Comparison of Various 50mm Lenses (2015), Saturn Images w/Summilux (2016)

- Appendix G: Comparison of 135mm Focal Length Lenses: A 135mm Lens Shootout! (2019)

- Appendix H: Comparison of Various Tele Lenses, 180mm to 400mm (2016)

- Appendix I: Effect of Pixel Size on Dynamic Range and Low Contrast Detail (2013)

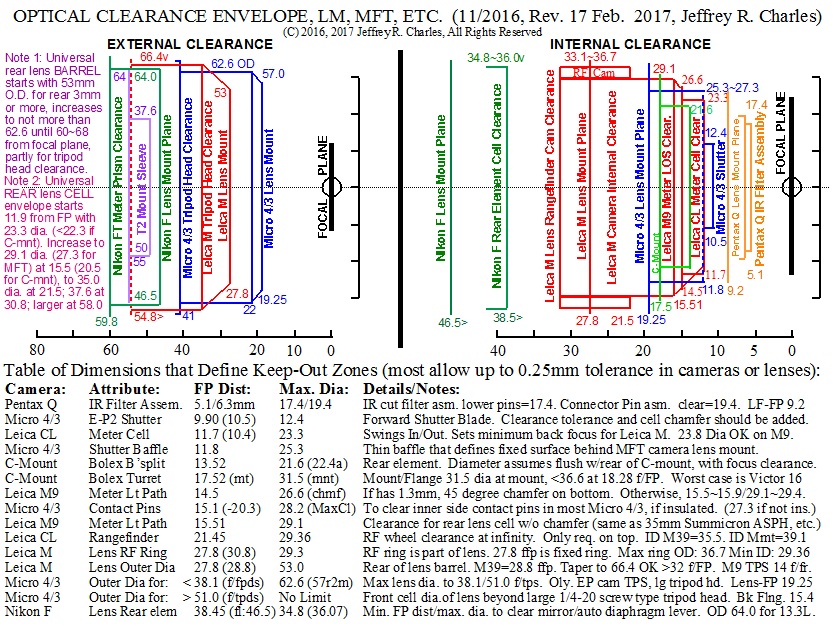

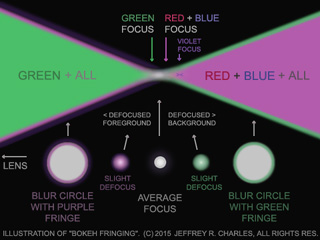

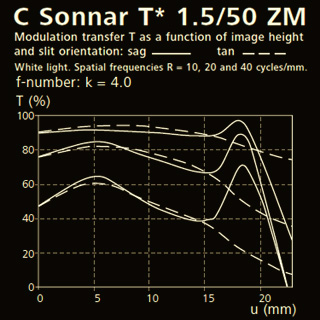

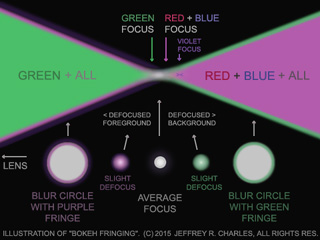

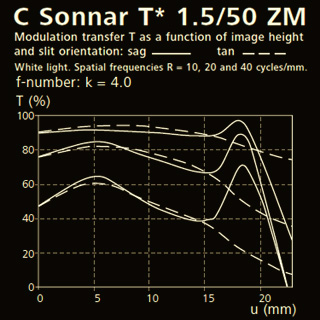

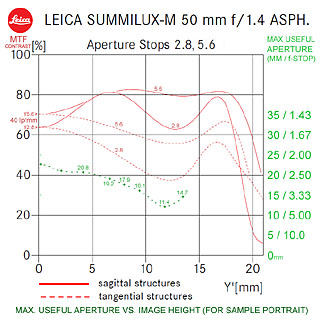

- Appendix J: Rangefinder Cam Diameters, Filter Sizes, Bokeh Fringing, and MTF basics

- Appendix K: Leica Optics and Images Compared to 4x5 Film, etc., Images (NEW 150503)

- Appendix L: Products and Versions it would be Nice to See Made by or for Leica, etc.

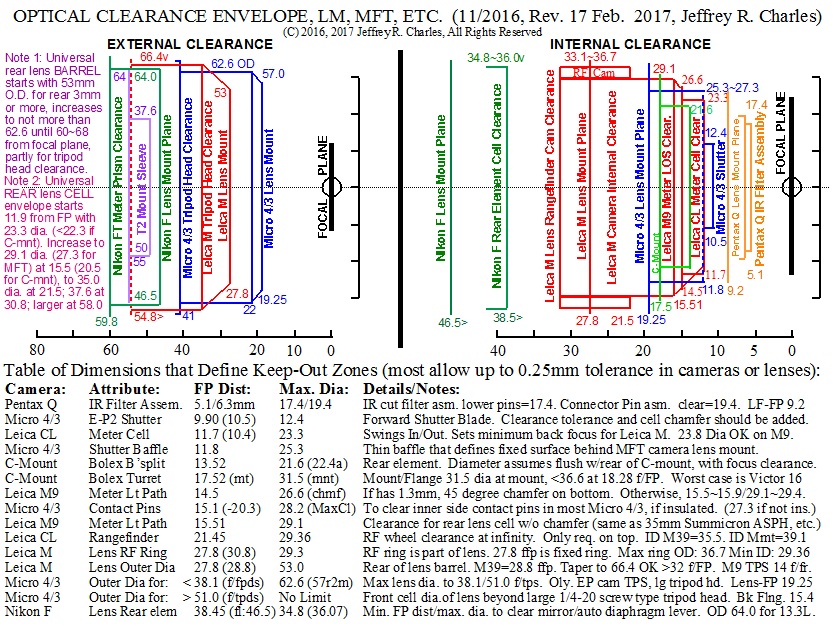

- Appendix M: Relevant Dimensions for Micro 4/3, Leica, Hasselblad, Etc.

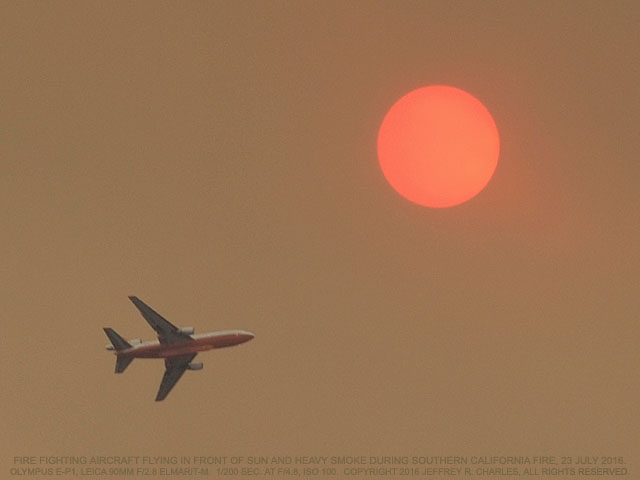

- Appendix N: Benefits and Perils of Buying Photo Gear You can't Inspect in Person (2016)

- Appendix O: References

- Appendix P: Photo Gear for Sale (to help fund the Leica)

- Appendix Q: Image Rotation in Some Browsers (some use EXIF data, ignore post processing)

Part 1: Leica M9 Review, Tests, and Comparisons. An Introduction.

Draft of Leica M9 Material Added as Separate Web Page: 23 Feb. 2013.

Copyright 2013-2017, 2021. Jeffrey R. Charles, All Rights Reserved.

This review covers the Leica M9 digital camera and a host of compatible lenses, accessories, and adapters. It is written from a user perspective, where the camera and lenses are used to take pictures. It dispenses with corporate mystique, or any notion of photo equipment being a status symbol. Emphasis is on the experience of using the camera and M mount lenses, and the results that can be obtained with them.

While the Leica M9 is the only camera covered in detail, this review has been periodically updated cover a wider range of Leica M lenses, keeping it relatively up to date in terms of lenses. Some of the lens reviews and comparisons may eventually be separated into different web pages, to reduce the (long) length of this one.

Other parts of this review cover certain lenses that were not originally made for the Leica M mount, but which can be used on Leica M cameras under certain conditions. One appendix compares performance of the Leica M9 and certain Leica lenses to the performance of larger format digital and film cameras.

Before getting into the review, it is important to note that some photos may not display properly in newer web browsers. When work on this web page began in 2013, it was written in HTML2 to make it viewable on older computers that lack the memory needed for newer browsers. This was to make it accessible to more people. Around 2018, Firefox and some other browsers began to only display pictures according to original image EXIF data, as opposed to the way images are rotated in post processing.

Overcoming this browser problem requires either editing the image EXIF tags, or, updating the HTML2 compatible web page code to accommodate CSS. Currently there is no available time to deal with either of these options. Therefore, several photos will display sideways or even upside down in some browsers. If this is ever corrected, it will be done in one of two ways: Editing the image EXIF tags, or, by opening a later version of this page in an old browser and printing it to PDF. Now, on to the review:

We will start with shortcomings of other cameras that ultimately led to my selecting a Leica M9 back in 2013. Other suitable cameras (certain Sony Alpha full frame and Fuji-X APS cameras) have become available since 2013. However, 2013 was when I was looking for a camera with what were, at the time, rare qualities. This time frame is the context of the present camera review. Over time, several newer lenses were reviewed in addition to the camera.

In 2012, I wrote a web page titled "Influence of Marginal Ray Angle to Anti Alias Filter on Digital Image Quality" which described some pitfalls of anti alias (AA) filters (and thick sensor filter stacks) when wide angle rangefinder lenses are used with certain digital cameras. Part of the present review web page (mainly older parts that were prior to "hands on" with the Leica M9) was initially an appendix to that one. Some of the lens test data has been accumulated since 2004, but was formerly unpublished. Material covering the Leica M9 camera and most Leica brand lenses is new to this web page.

In gradually writing the 2012 web page that described radial blur that occurs when fast f/ratio, short to medium focal length rangefinder lenses are used on Micro 4/3 cameras up to the Olympus E-P2 model, the conclusion was more or less that the Leica M9 was the best available solution to the problem, but that its price was prohibitive. This conclusion still stood in 2017, even after evaluation of newer Micro 4/3 cameras up to the Panasonic GX7, plus some Fujifilm X APS format cameras.

About a year after the original AA filter web page was written, the new price of a Leica M9 dropped a bit, and some dealers had demo models for a little less than the reduced new M9 price. A used M9 was getting to cost even less, but those carry risks in terms of a lack of warranty. However, by 2017, the price of a used Leica M9 began to be competitive even with some new high end name brand full frame DSLR cameras.

Ultimately, I decided to get a Leica M9 with the full 2-year warranty from an authorized Leica dealer back in 2013, then sell much of my other photo gear in order to restore assets from savings that had been diverted to get the Leica. It did not work out as hoped right off the bat because the new Leica M9 had some problems that needed to be corrected, so I had to keep using some of my old equipment for some time. But when the Leica M9 problems, including the dreaded sensor corrosion, were at last corrected in early 2017, I could at last use the Leica M9 as intended.

A great deal of other photo gear won't be missed in light of using the Leica, because I've gradually grown weak from a medical condition, to the extent that it's difficult to even carry or use the other cameras, some of which are physically larger and heavier. Some of my other cameras are small, but don't take good pictures compared to the Leica. I'll still use Micro 4/3 cameras, but mostly for grab shots and long telephoto pictures. A newer Fujifilm X APS format camera is also used because it is a good complement to the Leica M9 system.

The Leica M9 is a sizeable investment for a person such as myself who has made significantly less than six figures. Other than an automobile or house, the Leica M9 is the most expensive single item I've ever purchased in my lifetime by a factor of two. Therefore, some soul searching (and a lot of saving) was needed before I could acquire one. (The M9 body actually cost more than the combination of every car I've owned other than the most recent two!) It is hoped the Leica M9 will provide years of reliable service.

The Leica M9 was selected over DSLR systems for a number of reasons. Three of the most important are:

1.) The physical size of the camera (and camera system) is small enough that its size is rarely a consideration in whether or not to take it on trips or otherwise use it; and,

2.) Availability of sharp and fast (f/2 or faster) prime lenses having small physical envelopes.

3.) Familiar and simple manual user interface.

I also already had a few older Leica M lenses that I used on my Micro 4/3 camera. This meant that even if I bought only a Leica M9 camera body, I could still use it right away - with my existing older Leica M lenses. More M lenses could be considered after my wallet recovered from acquiring the camera. Another important feature is that the user interface for manually setting focus, shutter speed and f-stop is like that of film cameras I'd used for decades. To me, manual settings are simpler than numerous program modes, partly because manual settings have true cause and effect relationships.

Combined, the fast M prime lenses and compact camera size would make it possible to get shallow depth of field photos without using telephoto lenses. I was used to getting pictures like this with medium format cameras, but 35mm format DSLR lenses, including my old Nikon SLR lenses, were not quite good enough to provide both high resolution and the shallow depth of field results I was looking for. Details about shallow depth of field are in Appendix D (lens reviews), in the introduction for the 50mm f/1.4 Summilux-M ASPH lens.

The Leica M9 was selected over newer Leica models for reasons other than purely having a lower price than the newer digital M (also known as the Type 240) was expected to have, and now, as of mid 2013 and onward, has. Rather, other than the absence of an EVF accessory port, I actually prefer the Leica M9 or M9-P over most of the new Typ... models for a number of reasons. These include a frame line preview lever and passive illumination of the frame lines through a front diffuser window.

These viewfinder related features make using the Leica M9 more like using a Leica M film camera, and also make it possible to set up a shot before the camera is even turned on, which can save a lot of battery time. This probably will not be possible with the newer versions. Passive illumination of the frame lines also keeps them dim enough to use for framing piggyback astrophotography shots by looking at stars through the viewfinder.

The new Leica M10 and M11 restore the frame line preview lever and have a 0.73x viewfinder (compared to 0.68x in the Leica M9), and a shallower depth, all of which at least put them on par with the Leica M9. The superior high ISO performance of the M10 and onward is not a big deal for me, since I often use a low ISO setting and a tripod anyway.

Thus far, the Leica M9 has proven to be the easiest to learn digital camera I've ever had the pleasure to use. Other than a few menu items such as ISO and white balance, using the Leica M9 is almost like using a Leica M film camera. This makes its user interface familiar. A rangefinder camera is also something I can still focus accurately, unlike my diminished ability to focus an SLR in the absence of a strong magnifier.

In only a couple of months, the Leica M9 has made it possible to almost effortlessly obtain pictures I have not obtained with other cameras over the last few years. These include getting pictures of cloud formations before they disperse, capturing multiple hawks in a single photo, and even taking accidental pictures of a comet.

Part of the increased success in capturing short lived events may be because of how easy it is to use the Leica M9. You just turn it on, compose, focus, meter and shoot. It's that simple in many cases. There is no mental block about what menus you have to wade through while the opportunity for the shot you want slips away. The M9 just does what a camera should. It takes pictures, and pretty good ones at that. The Leica is a results oriented camera, not a process oriented bunch of lights and menus with a camera attached. In practice, setting the M9 takes only half as long as my Micro 4/3 camera does in manual mode.

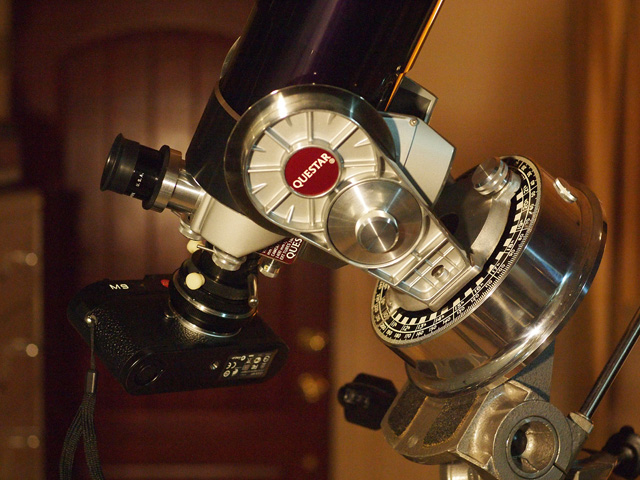

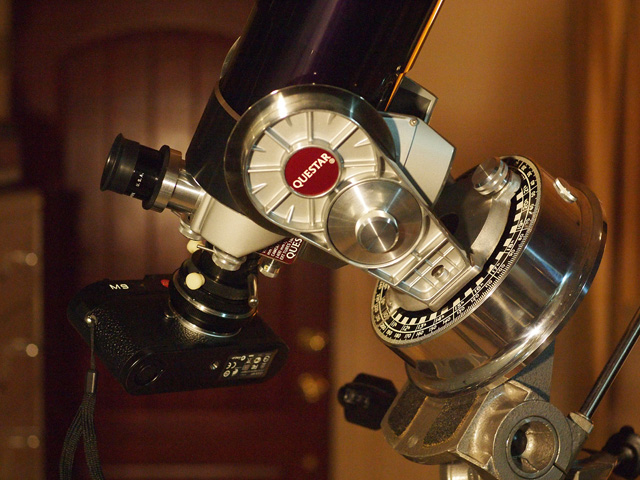

It has even been possible to take pictures through a telescope with the Leica M9, by using either a Visoflex or a different camera (such as a Micro 4/3 camera with an EVF or an SLR film camera with a strong focus magnifier) to frame and focus. I used similar techniques with a Leica M3 on long focal length lenses in the 1970's, since its shutter caused less camera shake than an SLR.

It is envisioned that this web page will be updated over time to include more Leica M9 sample photos and more consistent comparisons to other cameras. However, owing to the above medical condition that requires a lot of bed rest when I'm not at work, I often have only enough energy "overhead" for as little as an hour or two a week of discretionary activities like using cameras, writing web pages, or even housekeeping. Therefore, any updates could easily be many months apart and consist of only a few additional pictures or descriptions. The date of the newest revision is at the end, for reference.

1.1 Conventions

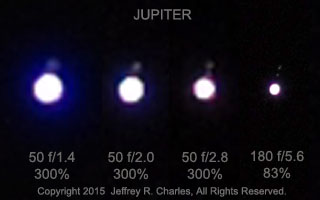

In the sample pictures the relative magnification will often be referred to as a given "percent crop". This relates to the pixel scale when a browser is set to display photos at 100 percent of the posted size. It is not an indication of the percentage of the original image format that is shown.

For example, the image scale of a "50 percent crop" is half that of the original image. A 100 percent crop is a direct crop from the original image that has not been scaled at all. A 200 percent crop is twice the scale of the original image, and so on. Some crops larger than 100 percent are included to allow for the reduced ability of some web browsers to display all detail in an original image at 100 percent. A larger percent crop also makes it easier to point out small details in the original image.

1.2 Down Sides, Most of which were Temporary:

Unfortunately, there appeared to be a few issues with my particular M9 camera.

1.2.1 Lens Mount to Focal Plane Distance:

As one who shoots both landscapes and astronomical photos, I quickly found that none of the 13 Leica M mount lenses I had (at the time I tested the M9 camera) would quite reach infinity focus on my Leica M9. These were not all Leica brand lenses, but some of them were.

Considerable testing (with the lenses, plus a fine ground glass on the back of my Leitz-Minolta CL film camera) appeared to show that the lenses were calibrated to within about 0.02mm of each other and with the Leica CL camera focal plane, but that the Leica M9 lens flange to focal plane distance could be at least 0.035mm too long at the center. There also appeared to be up to a 0.03mm (worst case) parallelism error between the lens flange and focal plane. This is 3 to 4 times as much error than I recall was advertised focal plane tolerance in the 1970's for Leica M film cameras.

It was hoped that these focal plane errors would just be temporary, but I did not get a chance to send the camera in to Leica USA for warranty service until it was just shy of one year old. The matter played out over a couple of years. The initial repair of early 2014 failed to correct the problems, and some aspects of the camera, including the rangefinder, were actually made worse by the early 2014 warranty service. After that, it took the better part of a year to get Leica to take a second look at it.

Fortunately, by early 2015, Leica USA corrected most of the issues that had gotten worse in the 2014 repair attempt, and they calibrated the camera using some instruments they said they didn't have in 2014. It was then possible to determine which of my lenses were consistent with Leica's reference lenses. The 50mm Summilux lens I acquired in 2015 tested within 0.002mm of their post-repair measurements, which is within the margin of test error.

The end result of the 2015 repair was that the camera's lens flange to focal plane distance was reduce to being only about 0.01mm too long at most, and it has been possible to get accurate focus via the rangefinder even with a 135mm f/2.8 lens. Details about the results are in Appendix B2.

This review previously included a detailed running account of events up to the early 2015 service, plus sample pictures from before and after the repairs. (This material is in Appendix A, Appendix B, and Appendix B1.) This was partly so Leica could reference technical details during service. Some of that older material is now gradually being removed. This is partly because, the usual point of a review is to assess how a camera performs when it is working properly.

Below, some tests done up through late 2014 assumed that the Leica M9 lens flange to focal plane error had been corrected by the 2014 warranty service. However, tests in late 2014 showed that incremental service on the lenses (more or less to make them agree with the camera) is what made the difference. This is known because lenses that were not serviced in this way still had about the same infinity focus error in M9 images as before the 2014 service, when set to their infinity stops. Material based on the former assumption is gradually being edited.

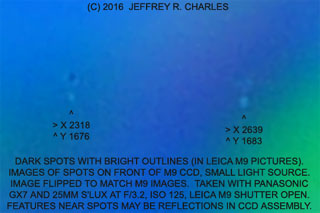

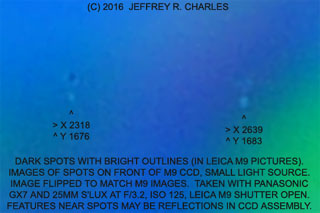

The original image sensor eventually experienced the dreaded "corrosion" problem, where coatings in the sensor filter stack develop flaws that are imaged in the picture as dark spots or clump of spots that are each surrounded by a brigher ring. Tests in Appendix B3 were performed after the sensor was replaced by Leica in 2017.

1.1.2 Astigmatism and Dimness in One Channel of the Rangefinder

As noted above, the rangefinder was degraded and misaligned vertically in the first round of service by Leica USA in 2014. This was never fully corrected, though Leica did do a better job of adjusting vertical alignment of the rangefinder in 2015.

1.2.3 Image Sensor Cover Glass Coating Corrosion

Like many Leica M9 cameras, my sample developed what is commonly referred to as sensor "corrosion" within less than 3 years. This was repaired in 2017, only shortly before the end of the time window in which Leica corrected this problem for free.

1.2.4 Sensor Cover Glass Causes SOME Radial Blur at Wide Apertures.

This is not a flaw unique to my particular Leica M9. It was found that the sensor cover glass causes some radial blur and image smearing at wide apertures, especially with wide angle lenses.

This blur and smearing at least seems to be a little more pronounced on the new replacement sensor, so I don't know if the sensor stack thickness changed between old and new M9 sensors. (Based on various articles, I think the old filter/cover glass stack was about 0.8mm thick.)

Specifically, most wide angle lenses must be used at f/3.4 or slower to eliminate radial blur or smearing around highlights that are imaged toward the edges of the frame. Radial blurring at wide apertures even happens in images with the 35mm f/2 Summicron ASPH lens.

For those who are interested, I found that it was possible (at least in 2013) to purchase the extended warranty on the Leica M9. Leica USA was initially unsure of the warranty availability in the U.S., but Leica in Germany informed me that it was, so I purchased the extended warranty on my Leica M9 at that time.

Before getting into the rest of this web page, the usual caveats: This is not a complete, formal, or comprehensive review like those at web sites dedicated to camera reviews, nor am I a professional camera reviewer. This review is instead a compilation of my user impressions of the Leica M9 and any lenses or accessories that may also be mentioned. Unless specifically noted otherwise, where any details about any product are mentioned without quoting a manufacturer, such details were often obtained through inspection or measurement of available product samples, and do not represent any manufacturer's official specifications.

Leica M9: A Compact and Portable Camera System

In the context of when the first version of this section of the review was written in 2013, the Leica M9 is a unique approach to full frame digital photography. Rather than being a typical digital camera with a myriad of confusing program modes that vary from brand to brand, the Leica M9 is based in large part on the manual user interface familiar to Leica M film camera users.

There is no auto-focus or program exposure, but there is something better, and that is simplicity of operation for those used to manual film cameras! Since it has a full frame (36x24mm) image sensor, even the coverage of familiar lenses is retained. The Leica M lenses have real mechanical manual focus, and manual aperture (f/stop) controls.

The Leica M9 is also very compact, being quite small in comparison to full frame digital SLRs. The M9 is comparable in size to a Leica M film camera. For those unfamiliar with Leica film cameras, the Leica M9 is about the same size as the vintage Pentax Spotmatic single lens reflex (SLR) camera body, and is smaller than the Nikon F2 SLR film camera. If these are not familiar, the M9 is only about 2 cm wider, 1 cm taller, and a little under 1 cm thicker than a Micro 4/3 camera such as the Olympus E-P1, E-P2, or E-P3. It also has a solid feel and the physical Leica M mount lens sizes are even smaller than many Micro 4/3 digital lenses.

The Leica M9 is a rangefinder camera rather than an SLR, yet it uses interchangeable lenses. The rangefinder eliminates the need for the mirror box used in SLR cameras, so the M9 has a compact size even though it uses a full frame 36mm x 24mm image sensor.

A rangefinder is a very precise method of focusing. Rather than watching an image mush in and out of focus as with an SLR camera, a rangefinder provides two sharp images that are superimposed over each other. The images move horizontally with respect to each other as a lens is focused, and merge into a single sharp image at the focus distance.

Since the Leica M9 viewfinder does not "look through" the camera lens, its finder instead has frame lines superimposed over a clear view of the subject to show the coverage of different lenses. When a compatible lens is attached, the camera automatically brings up the appropriate pair of viewfinder lines, one of which matches the lens field of view.

The Leica M9 viewfinder line pairs are for 28mm and 90mm, 50mm and 75mm, and 35mm and 135mm. These frame line pairings make it fairly obvious which frame line corresponds to a given lens, with smaller frame lines being for longer focal length lenses.

For lenses wider than 28mm, a matching viewfinder attachment is used in the camera's flash shoe. Zoom lenses (in the usual sense of the word) are not supported, because the viewfinder frame lines show only specific focal lengths. Exceptions are that Leica makes two zoom lenses, but each of these are intended to be used at only 3 focal length settings.

Even though a wider 21mm lens would normally require a separate finder attachment, I delighted to find that the full extent of the Leica M9 viewfinder (the part outside the 28mm frame lines) covers almost exactly the same field of view as a 21mm lens, so I can use the 21mm without attaching its accessory finder. It is necessary to move my eye around to see the edges of the M9 finder, but it is faster than using a separate finder. It was also possible to code most of my lenses so they are automatically recognized by the camera.

One limitation of a rangefinder camera is that focusing becomes less accurate when the lens focal length exceeds about four times the width of the image format. For this reason, 135mm is the longest lens that can usually be used on a rangefinder camera, at least when the rangefinder is the only means of focus information. However, it is possible to use longer focal length lenses and even telescopes by using a different camera (such as a low cost SLR film camera) to focus, then switching the Leica body onto the lens or telescope to take the picture.

Leica also made an optical flip mirror attachments called a "Visoflex" back in the 1960's or even earlier. Several models were made. If the eye level finder is used, only the Visoflex III is compatible with the Leica M9. The Visoflex converts a Leica M camera to a Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera that can be used with certain long focal length lenses, or for macro photography with shorter lenses.

The newest version of the Visoflex flip mirror, the Visoflex III, is compatible with the Leica M9. I be tried it on the M9 and it worked OK, but attaching and removing it is a little tedious. The physical depth of the Visoflex is deep enough that infinity focus is only possible with certain telescopes and a limited number of telephoto lenses. Many newer Leica M cameras (not the M9) are compatible with an electronic eye level viewfinder (EVF) that can be used with the camera is in "Live View" mode.

It is also possible to use moderately longer focal length lenses at infinity on the M9 without going to the bother of swapping camera bodies or using the Visoflex, since the lens infinity stop can be used to set focus. However, it is necessary to set the Leica rangefinder (and thus its parallax correction) to infinity so the rangefinder patch can be used as a reference for centering of the subject. This is not as easy as it sounds with available adapters. However, it is possible with an appropriately modified adapter. This is covered in a later section.

Introduction of a newer version of the Leica digital rangefinder, the M (i.e. Type 240) was expected only weeks after this web page was first published. (Reviews of the M began to appear when some of the first revisions of this M9 review were made.) The M240 can be used with an optional electronic viewfinder (EVF) that is similar to the one for Olympus Micro 4/3 cameras up through the E-P3. The EVF supplements the rangefinder and provides compatibility with a wider range of lenses, plus making it easier to use a digital Leica M camera on telescopes and microscopes, etc. (Update: The newer Leica M10 uses an EVF similar to that for the Olympus E-P5 M4/3 camera.)

The Leica M9 digital camera has an unusually high price, and the new Leica M lenses are also quite expensive. However, the M9 has been implemented in a way that allows it to be used with almost every Leica lens made back to about 1950. (There are only a few exceptions that include certain wide angle and collapsible lenses.) Many of these older lenses are much more affordable, but still quite good. Newer third party Leica M mount lenses such as those made by Voigtlander-Cosina (VC) and Zeiss (said to be made at the same factory as VC lenses) can also be used on the Leica M9 and probably newer Leica cameras as well.

The other lens options (older used Leica lenses or the newer VC and similar lenses) make it possible to acquire a decent range of focal lengths at reasonable cost, even when compared to the cost of DSLR lenses or recent Micro 4/3 prime lenses. These lower cost M mount lenses have the effect of making the cost of a workable Leica camera system more competitive, though most other brand M mount lenses are not as good as the Leica brand lenses.

Still, even the low cost off brand lenses on the Leica M9 seem to produce better photos than most smaller format digital camera lenses do on their respective cameras. The smaller size of the Leica M9 system compared to a full frame DSLR system (or more recently, to other full frame mirrorless camera systems) may be decisive in whether or not it is taken on different types of trips, etc.

Compact Leica M9 Camera System (Three Iterations)

Three Iterations of a Compact Leica M9 Camera system.

© Copyright 2013 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

First Two Versions of Leica M9 System (Empahsis on Low Cost and Third Party Lenses):

LEFT: The first iteration of the Leica M9 system included two Leica brand lenses and several third party lenses. The lenses include Voigtlander-Cosina (VC) 21mm f/4, 28mm f/2, 40mm f/1.4 (on camera) and 75mm f/2.5 lenses, and a collapsible Industar 50mm f/3.5 lens. The Leica brand lenses are the 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit and the 135mm f/4 Elmarit, to the right of the camera. The Olympus flash was modified to remove all pins except the center pin that's for basic flash synch. Its hot shoe contacts are isolated from high voltage circuits, so only a 3 Volt potential is between them. All of the items except the 28mm and 90mm lenses fit in a small customized Leica system case.

RIGHT: The second system iteration shows that the Leica M9 and a good selection of lenses can fit in a small space. Items here (lenses listed from left to right) include a Voigtlander (VC) 12mm f/5.6 Ultra Wide Heliar lens, a VC 21mm f/4 Color Skopar, a VC 28mm f/2 Ultron, a VC 40mm Nokton, a Zeiss 50mm f/2 Planar ZM (on the camera), a Leica 75mm f/2.5 Summarit-M, a 90mm f/2.8 Tele Elmarit M, and a 135mm f/4 Elmar lens. Accessories include filters, extra caps, battery and charger with cord, auxiliary viewfinders, a short cable release, and a VC light meter for low light situations. The charger cord is short, to easily fit in the case. All items in this system except the 21mm finder, 28mm f/2 Voigtlander lens (left of camera) and the 90mm Tele Elmarit-M lens with rubber hood (second lens from right) fit in a small modified hard Leica film camera case.

|

|

Third Version of Leica M9 System (More Leica Lenses After Wallet Began to Recover):

(This picture is a PLACE HOLDER, and does not show the full system)

This third and most recent system iteration also shows that the Leica M9 and a broad selection of lenses can fit in a small space. Items here (lenses listed from left to right) include a Voigtlander (VC) 10mm f/5.6 Hyper Wide Heliar lens (with a Fuji X adapter used as part of its rear cap), a VC 12mm f/5.6 Ultra Wide Heliar lens with its viewfinder, a VC 21mm f/4 Color Skopar, a 7Artisans 28mm f/1.4, a Leica 35mm f/2 Summicron-M ASPH (on the camera), a Leica 50mm f/1.4 Summilux-M ASPH, a Leica 75mm f/2.5 Summarit-M, a 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit M, and a 135mm f/3.4 APO Telyt-M lens. Accessories include filters, a Leica SF-24D flash unit with accessory lenses, extra caps, battery charger (charger uses short plug adapter instead of cord), extra batteries, auxiliary viewfinders, a short cable release, and a VC light meter for low light situations. All items in this system except the 10mm f/5.6 Voigtlander lens, 21mm finder, 28mm lens (left of camera) and 90mm Elmarit-M lens (second from right) fit in a small modified hard Leica film camera case.

* When the M9 camera is in the case, the 35mm or 50mm lens is usually attached, then most of the other lenses are paired on double sided rear lens caps. Any two of the three lens pairs can fit in the case, and the other pair is kept in an external lens case. The lens pairs are: The 21mm with the 135mm, the 28mm with the 90mm, and the 35mm or 50mm with the 75mm.

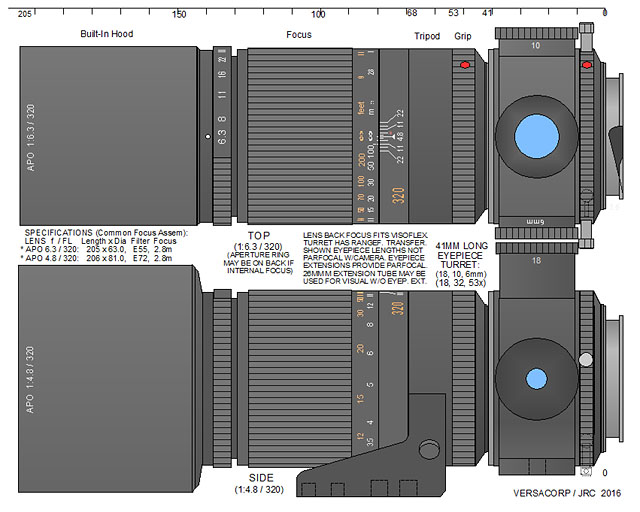

* A Visoflex III with 65mm f/3.5 Type II Elmar and 280mm f/4.8 Type III Telyt lenses are kept in separate cases. Also, a Voigtlander 180mm f/4 APO-Lanthar, a Leica 250mm f/4 Telyt-R, a Nikon 400mm f/5.6 ED Nikkor, and a small Borg telescope are all occasionally used with custom adapters. This comprises the third, and probably the last, iteration. Lenses are reviewed in a later section.

|

Compatibility with Vintage Compact Leica System Cases

The Leica M9 is almost as compact as a Leica M film camera, with the main difference being a little added depth. The added depth is enough that the M9 will not fit all vintage cases made for M film cameras, unless of course the case is modified.

Another consideration is that the front lens in the M9 viewfinder is not recessed at all, so the viewfinder side of the camera cannot safely slide in and out of the camera recess in a vintage case, unless this aspect is modified too. Over time, I developed two generations of modifications to a vintage Leica system case. The first generation (not pictured) was just to test the concept. I kept only accessories in the first version due to the flush viewfinder lens issue.

The second generation of the case modification was finished in March, 2014. It provides a larger pocket for the camera body, and the viewfinder corner of this pocket has a padded slope that the top part of camera contacts at only its top edge, as opposed to both the top edge and the front surface of the viewfinder glass. This prevents direct contact between the vulnerable viewfinder glass and the original case divider, to reduce the risk of scratching. All other modifications are in the form of a stand alone cloth covered insert that is simply slipped into the case, and which is held in place by its own fit to the case interior, plus a tab that slides behind part of the camera pocket.

The second generation case modification is shown below. It is a significant improvement over the first in that it provides more space for the camera body, better padding between items, and accommodates the camera with a lens up to 75mm focal length attached. The latter was accomplished partly by staggering the lens stacks, rather than keeping them next to each other along one side of the case, as in the first modification. In this version, all dividers are attached to each other for better stability. An added feature of the new insert is that it can be removed and rotated 180 degrees, to provide an arrangement similar to the first version.

As with the first version, two-ended rear lens caps such as those Leica has made for decades are an important part of getting the whole system into such a small space. It is an even tighter fit with the 50mm f/1.4 lens, but still works. The fit of the vintage case is a bit tight for so many items, but it is workable, and the object was to fit an existing case rather than starting from scratch. The case got a little more crowded when I switched from a compact customized Olympus FL14 flash to the larger Leica SF-24 flash.

A case interior that is about 5mm larger in all directions would provide a better fit and permit wider tolerances for the insert. An interior at least 8mm larger in all directions would accommodate some larger diameter high speed lenses such as the 35mm Summilux or the 75mm Summicron. A considerable enlargement of the case would be needed to accommodate a Noctilux, while still having room for the other lenses. If the lens stacks were not staggered, it would be possible to carry a relatively large flash unit in the case, but this would require that the case be about 20mm longer (end to end) in order to still permit the camera with an attached 75mm lens to also fit in the case.

If Leica or another manufacturer made a case and insert similar to this that was 15mm wider, 10 to 15mm taller, and 8 to 10mm deeper in its shortest dimension, the lens stack insert could have considerable padding and there may also be room to leave a vented lens hood on a 35mm to 50mm lens when it is kept on the camera. It would also accommodate a larger flash unit. A little added height would permit lenses other than the compact 21mm f/4 to be stacked with a 135mm f/4 Elmar or 135mm f/3.4 APO lens, which would speed up changing between the 21mm and other lenses.

Simple Modifications for Leica M System Case, to Work with Leica M9. Second Version.

Simple Modifications for Leica M System Case, to work with Leica M9.

© Copyright 2014 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

Custom Cloth Covered Metal Camera Case Insert Accommodates Camera and Six Lenses!

LEFT: The Leica M9 and all lenses and accessories shown here fit in the modified hard Leica system case. I already had some of the shown lenses to use with a Micro 4/3 camera, so I didn't need to pick up many extra items to have a relatively good selection of lenses for the Leica M9. I eventually added 35mm f/2 and 50mm f/1.4 ASPH lenses, but not until after my wallet finished licking its wounds from acquiring the camera.

RIGHT: As with the first generation of my modification, the key to getting the Leica M9 and so many lenses and accessories in the small Leica case is the custom insert that dominates the inside of the case. The insert and associated dividers isolate the two lens stacks from each other, and from other items. This insert is made of a combination of sheet metal and stiff cardboard, padding in some places, and a cloth covering. I used the shown thick green cloth because I had a lot of it around. All dividers are attached to the insert, and some of these are hinged to facilitate different equipment configurations in the case. The flap just right of the camera recess protects items stored below it.

|

|

|

Vintage Leica Case and Custom Insert Accommodates Leica M9, 6 Lenses, Charger, Flash.

LEFT: Here, the case is shown partly populated. The flap toward the left folds down over the top of the 12mm Voigtlander lens. Larger lenses can be stored on their side where the 12mm and filter are shown. Other items can be added on top of the charger (shown top center) and over the small light meter shown at lower right. A compact AC plug for the charger is in the case, but is under some of the other items.

RIGHT: In this picture, the case is fully populated, including a small flash and the viewfinder for the 12mm lens. The following items are all in this small case:

* Leica M9 camera with grip, strap, and 50mm f/2 Zeiss Planar ZM lens attached is at left.

* 12mm f/5.6 Voigtlander lens is stored under the 50mm lens, protected by a hinged divider.

* 75mm Summarit-M and 35mm f/2 Summicron-M Asph, with 2-ended rear cap, are near center.

* 135mm f/4 Elmar and 21mm f/4 Voigtlander lens, with 2-ended rear cap, are at upper right.

* Spare rear cap and a body cap are under the 35mm and 75mm lenses.

* Small flash (Olympus FL-14, with the proprietary pins disconnected) is at top center.

* A couple of filters are under the flash, next to the 12mm lens.

* Viewfinder for 12mm lens and a small light meter (under the finder) are at lower right.

* Leica charger and a compact AC plug are under the flash at top center.

* Two spare M9 batteries. One is below flash. One (and 2 AAA batteries) is under finder at right.

* A short cable release can be stored by the battery at upper left.

* One memory cards can be stored under the camera recess, and another stored at lower right.

* Note: A 90mm Tele-Elmarit-M and 28mm f/2 lens stack can be swapped for either lens pair.

|

|

|

Custom Case Insert Configured to Accommodate a 6 (Left) or 8 (Right) Lens System.

LEFT: In practice, the flash is kept in a soft case, all lens caps are used, and the lens stacks and a few other items are kept in plastic bags as shown. The plastic bags make it easier to access items that are near the bottom of the smaller compartments. When the camera is placed in the case, the camera strap is nested between the camera and the center lens stack. There is quite a bit of strap material here because I keep both a neck strap and wrist strap attached to the camera at the same time. When the camera was serviced by Leica, the vulcanite was replaced with the shown covering that looks similar (compare to vulcanite pictured on the grip), but has less contour, a flatter finish, and a more rubber-like feel.

RIGHT: An alternate configuration for the case, easily implemented by just bending some of the hinged dividers, is to carry more lenses and accessories, while carrying the camera and one lens separately. Here, two additional lenses (28mm and 90mm) and more filters are added. This accommodates an eight-lens system, but provides less free space when swapping lenses. The flash is under the filters at left.

|

Initial Results with the Leica M9: Almost no radial blur

(Plus some results after warranty service to correct infinity focus problem.)

The first Leica M9 images below are taken under similar circumstances and at similar f/ratios as the Micro 4/3 images that showed (in my 2012 web page about radial blur with anti alias filters) serious radial blur problems. It is evident that the lack of an Anti Alias (AA) filter in the Leica M9 (plus other aspects, including a larger sensor) can provide far better results, though there is obviously aliasing on certain subjects. As with the Micro 4/3 tests, a tripod (Gitzo Reporter or heavier) was used for all test pictures, even with wide angle lenses or fast shutter speeds.

Before the Leica M9 was serviced, temporary lack of infinity focus with the Leica M9 caused blurring on distant subjects with fast wide angle lenses, which wasn't too good. The blur from defocus at long subject distances was then about a third as severe as the radial blur that was noted with the same lenses on a Micro 4/3 camera.

After the Leica M9 was returned from service in March 2014, infinity focus was possible with most lenses. All Leica brand lenses made after the early 1980's reached infinity focus on the camera, but some older Leica lenses and a few third party lenses (those more than 0.04mm from reaching infinity focus before the M9 was serviced) still did not quite reach infinity focus. These lenses were tweaked to reach infinity focus on the camera as serviced, which also matched their infinity stops to the newer Leica brand lenses. Unfortunately, the Leica M9 rangefinder came back misaligned in the vertical direction to an extent that critical focus is difficult to say the least. That is covered in Appendix B1.

The VC 28mm f/2 used for the tests below was one that needed some tweaking. After its infinity stop was adjusted, the imaged quality of distant subject matter, including the palm tree trunk (at the right in each picture below) almost doubled in comparison to when the same lens was used at the same f-stop before the M9 was serviced.

Since the Leica M9 can now achieve infinity focus with most lenses, radial blur comparisons can be made to a Micro 4/3 camera having an anti-alias filter. With the same 28mm f/2 manual focus lens, results with the Leica M9 are nearly ten times better than the average Micro 4/3 image from my previous radial blur tests, when the palm tree trunk image is positioned the same 8mm physical off-axis distance in both cameras. A factor of ten improvement over the off-axis Micro 4/3 images is about as good as the theoretical limit of performance, given the Leica M9 pixel size, etc.

After service, the best case off-axis Leica M9 results are close to 10 times better than the average Micro 4/3 image with the same lens and f/ratio, which certainly isn't bad. This is almost entirely due to the Leica M9's lack of radial blur that is probably caused by the anti-alias filter in the Micro 4/3 camera. The Leica M9 results are also over four times better than the best case Micro 4/3 image with the same lens and f/ratio, where focus was adjusted in the Olympus EVF, with the magnified view being decentered to enlarge the palm tree trunk. To see the difference, compare the top Micro 4/3 image in the second image table below to the bottom Leica M9 image in the third image table.

In addition to comparing moderate focal length Leica M9 and Micro 4/3 images, a few longer focal length (>400mm) images are included in the astrophotography section and accessories section. To take these pictures with a Leica M9, I used a techniques similar to some I used in the 1970's to take long focal length (up to 1600mm) pictures with a Leica M3 film camera.

One such method is to frame and focus the image with an SLR camera having a strong critical focusing magnifier, then replace the SLR with the Leica body and an adapter to take the picture. A modern day version of this is to use a digital camera having an EVF as the focusing device. Other methods are covered in the "Using Various Accessories with the Leica M9" section.

Using a separate camera to focus was practical even in the 1970's because a Leica M caused less camera shake than a typical SLR. There is less reduction of camera shake with the Leica M9 because its shutter blades move about 2.4 times faster than the shutter curtains in a Leica M3 to provide a faster X-synch speed, and probably to facilitate the 1/4000 second shutter speed.

The mechanical Leica Visoflex flip mirror can obviously be used with telescopes having adequate back focus, but camera body swapping is an effective way to get long focal length images using camera lenses that lack adequate back focus for a Visoflex. I hope to eventually replace the SLR body with a more compact ground glass attachment having a strong magnifier such as a Peak 15x loupe I use when critically focusing a Hasselblad.

The EVF of the digital M would simplify long focal length photography, but for a savings of over $2k, I can put up with camera swapping or a Visoflex unit. This is partly because about 90 percent of my pictures have been taken between the focal lengths of 21mm and 135mm, even at times I had access to a wide variety of lenses outside this range. Thus, focal lengths other than those supported by the M9 frame lines or a shoe mounted finder are not used that often for the type of pictures I take.

Radial Image Blur Comparisons:

Radial blur comparisons between Micro 4/3 and Leica M9, Context.

© Copyright 2012, 2013, 2014 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

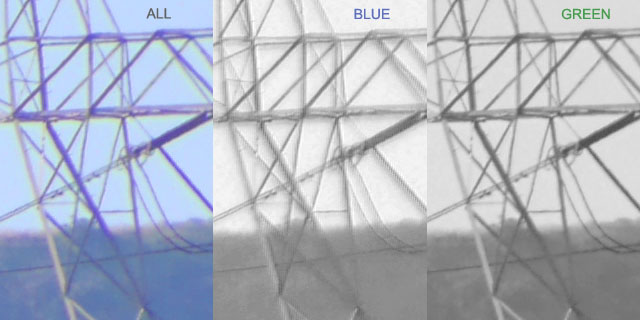

Radial Blur from Anti-Alias Filter (Upper Right), from 2011 Test with Micro 4/3 Camera.

To compare radial blur, we will start with Micro 4/3 images from the 2012 tests, all taken with a VC 28mm f/2 Ultron lens. This picture shows the entire width of the Micro 4/3 image from which the next two examples of radial blur will be cropped. The points of interest will be the right sides of the palm tree trunk and the roof air conditioner at the extreme right of the picture, wires from the power pole transformer left of that, and the green tree near center. The camera is an Olympus E-P2 and the lens is a Voigtlander (VC) 28mm f/2.0 Ultron. The VC 28mm f/2 lens has remarkably low veiling flare (even less than the 35mm f/2 Summicron-M ASPH), which can reduce shadow detail captured in backlit situations such as this, but which is very helpful in most other situations. Compared to Micro 4/3, Leica M9 covers about twice the field of view with a given lens, due to its larger sensor (36x24mm versus 17.3 x 13mm). The best comparisons below were made almost two years after acquiring the Leica M9. This is because the Leica M9 did not initially allow any wide angle lens to focus even as far away as the palm tree at right until it was serviced twice by Leica.

|

Radial Image Blur Comparisons vs Focus Distance, Micro 4/3 Images:

Radial blur comparisons between Micro 4/3 and Leica M9. These examples of strong off-axis radial image blur are with an Olympus E-P2 camera, using the same Voigtlander (VC) 28mm f/2.0 Ultron lens that was used for my 2012 blur tests. Apertures used are f/2.0 and f/2.4.

© Copyright 2012, 2014 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

Radial Blur with M4/3 Camera: 28mm f/2 Ultron Lens Focused on Tree Trunk (Right).

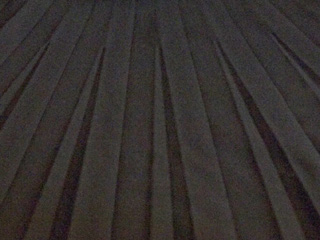

This image is cropped from the right side of the above scene. Here, the lens is focused near infinity, between the distance of the green tree at the left and the palm tree at the extreme right. Radial blur in the original 12MP image from the Olympus E-P2 camera is more than 13 pixels wide on the right side of the palm tree trunk, and almost as wide on the right side of the roof air conditioner. The blur is even wider at the corners. However, the blur width decreases toward the center of the original picture, where it is absent on the green tree at left. Note that the palm tree at right is in focus, but light from the background sky is blurred toward the center of the image, and thus over the palm tree trunk, probably by the camera's anti-alias filter. The scale of this image is about 43 percent of the original, so flaws are large enough to be obvious without pixel peeping. Most blue in the backlit wires is from the sky being blurred over them rather than from lens aberrations. Exposure at ISO 100 is 1/4000 sec at f/2.4.

|

|

|

Radial Blur with M4/3 Camera: 28mm f/2 Ultron Lens Focused Closer than Tree Trunk.

In this image, the lens is focused slightly in front of the palm tree, with best focus on the foreground telephone pole. Setting the focus closer reduces the width of the blur at the palm tree trunk distance by almost half, at the expense of some de-focus on the green tree at left (which is near the center of the original picture) and objects beyond it. The exposure at ISO 100 is 1/4000 sec at f/2.0. In spite of the wider f/2 aperture, the focus change reduced the off-axis blur to less than that of the image taken at f/2.4. Backlighting was less intense for this image, but blur width is relatively independent of backlight intensity.

|

Radial Image Blur Comparisons, Leica M9 Images. Almost No Radial Blur!

(Top image taken before service of M9, when good infinity focus was not possible.)

Radial blur comparisons between Micro 4/3 and Leica M9. These examples of very low Off-axis radial image blur are with a Leica M9 camera, using the same Voigtlander (VC) 28mm f/2.0 Ultron lens that was used on Micro 4/3 cameras for similar tests. Both images taken at f/2.4.

© Copyright 2013, 2015 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

Reduced Radial Blur with Leica M9: 28mm f/2 Ultron Focused Closer than Tree Trunk.

This image with the Leica M9 was taken prior to service, so the lens flange to focal plane distance is a little too long to allow the lens to reach infinity focus. The palm tree trunk at right is positioned at the same 8mm off-axis distance on the focal plane as for the Micro 4/3 images. The Leica M9 has a full frame sensor, so the tree appears closer to the center of the format. The position in this cropped image is similar to that in the above Micro 4/3 images. The same VC 28mm f/2 lens is used. The Leica M9 has very little radial blur, but its higher contrast at the Pull 80 ISO setting blows out the sky under lighting conditions similar to those for the Micro 4/3 images above. Here, the Leica M9 it fails to allow the 28mm lens to focus as far away as the palm tree trunk at right, even with the lens set at infinity. This prevents a sharp wide aperture image, hindering accurate assessment of radial blur. In this image, blur in the palm tree trunk from defocus is almost a third as severe as radial blur is in the optimized Micro 4/3 image above. Trees in the distance are even more blurred. The exposure at ISO 80 is 1/4000 sec. at f/2.4. This crop is about 65 percent of the original image scale. An improved image, taken after the camera was serviced, is below.

|

|

Reduced Radial Blur with Leica M9: 28mm f/2 Ultron Focused on Tree Trunk (Right).

This image with the Leica M9, taken after service, also places the palm tree trunk image 8mm off-axis on the focal plane. The same VC 28mm f/2 lens is used. The light is more favorable, so the sky is not blown out at the Pull 80 ISO setting. With infinity focus now possible, it is obvious that the Leica M9 has very little radial blur. Here, the 28mm VC lens focuses as far away as the palm tree trunk at right, providing a sharp wide aperture image. In this image, the tree trunk is not blurred much at all, and appears to be resolved nearly ten times better than the average blur in the top Micro 4/3 image on the previous table. Trees in the distance are also well resolved. The exposure at ISO 80 is 1/4000 sec. at f/2.4.

UPDATE 1: It was later found (gradually, by Nov. 2014) that service on the lens is what made the most difference for infinity focus, and that Leica's 2014 service on the M9 camera did not fully address the issue. Service on the lens had been done after the first test to make its infinity focus almost agree with the M9 camera, at the expense of causing the lens to focus slightly past infinity on my Leica film camera. Things were considerably better after Leica's 2015 service.

UPDATE 2: After the original Leica M9 Sensor (which developed corrosion) was replaced in 2017, images with this lens have had more radial blur, but not as nuch blur as with Micro 4/3 cameras.

Note: Add image of same test with same lens, but with replacement Leica M9 image sensor.

|

Moire, Green Stripes, Hot Pixels, Other Artifacts, and Sensor Corrosion

The Leica M9 initially exhibited several artifacts, while others did not appear until well after the camera was serviced by Leica in early 2014. Artifacts such as aliasing are to be expected in a camera having no anti-alias filter. However, other artifacts, including the green stripes or green pixel blocks next to saturated areas, seem unusual. The green stripe artifacts only occur under very specific conditions.

Aliasing

There is a tradeoff to doing without an anti-alias filter in order to prevent off-axis radial blur with rangefinder lenses, and that tradeoff is aliasing, or moire. The Micro 4/3 cameras tested with rangefinder lenses to date (Olympus E-P1 and E-P2) have about the same amount of radial blur (pictured above), but only rarely exhibit moire in the image.

The Leica M9 does not have any image flaws that have been identified as radial blur, though there have been rare instances of blue fringing and faint double imaging near the edge of the picture, neither of which appear to be attributes of the lenses used. Images at the same distance off-axis that would result in radial blur on the Micro 4/3 format show almost no obvious blurring flaws that are not an attribute of the lens. However, images of certain subjects do have moire.

In the examples below, moire appears in the image of the off-white cloth cover on the small speaker. Weave in the cloth is on a hexagonal pattern and has a 1.2mm interval. This speaker was imaged about 7mm off-axis when taking pictures of a clock that appear later sections. When a 35mm lens was used, the Leica M9 camera was about 4.2m from the speaker. When a 40mm lens was used, the distance was about 4.8m. At the Leica M9 focal plane, the lens images the weave on about a 10 micron interval, and a somewhat smaller horizontal interval (inadvertently, an interval similar to the camera pixels!) when the oblique angle of the speaker is taken into account. The result is moire.

The obvious moire pattern on the speaker cloth consists of an oval well left the center, which is surrounded by oval rings having a magenta cast. A second moire pattern, consisting of arcs centered around a point below the speaker, is superimposed over the oval pattern in the picture with the VC 40mm Nokton, but not in the photo with the 35mm Summicron, maybe because of a slight difference in the original image scale. Color moire is also visible around the top edge and the center ring of the brass plate in the Nokton picture.

Since images from Micro 4/3 cameras having anti alias filters provide good central resolution with rangefinder lenses, and because moire is generally most obvious near the center of the picture, the notion of a radial gradient anti-alias filter readily came to mind right after I took a few pictures with the Leica M9. Such an anti-alias filter could be almost as strong as that in my Micro 4/3 camera at the center, then gradually diminish in intensity with increased off-axis distance. For a rangefinder using fast f-ratio lenses, the anti-alias effect would need to begin to taper off significantly by 5mm to 6mm off-axis, and become relatively insignificant at an off-axis distance of about 10mm or slightly more, in order to reduce aliasing near the center, yet not cause blurring with wide angle rangefinder lenses. These off-axis distances can be increased for SLR lenses.

Moire with the Leica M9.

Moire with the Leica M9, inadvertently imaged while testing various lenses.

© Copyright 2013 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

| Moire with Leica M9 and 35mm f/2 Summicron-M ASPH lens, working at f/5.6. |

Moire with Leica M9 and 40mm f/1.4 Voigtlander (VC) Nokton MC lens, at f/5.6

|

Intermittent Horizontal Green Stripes Next to Saturated Parts of Image

Before acquiring a Leica M9, I had seen some posts that discussed subtle stripes in certain early Leica M9 images, and had looked at a few examples of such images. Later posts appeared to indicate that Leica had corrected the problem. When I got my new Leica M9 in early 2013, it did not exhibit these striped artifacts under any conditions. After the camera was serviced by Leica in early 2014, it began to exhibit such artifacts photos of strongly backlit subjects on rare occasions, with some artifacts not being very subtle.

The striped (and in some cases even rectangular) green artifacts occur only when something in or near the field of view is bright enough to locally saturate part of the image, and when such an object is located either right at the very edge of the picture, or slightly outside the edge of the picture. The artifacts are not optical, since the boundaries are too well defined. In some cases, such as in the right example below, the artifacts are large and obvious, to an degree that renders a picture unuseable. When the camera is positioned at only a slightly different angle with respect to the subject, the artifacts usually do not appear at all. Since these artifacts appear only in rare circumstances, it is possible that the camera had this anomaly all along, but just was not noticed before.

Since I acquired the camera, the stripes have only appeared in 5 or 6 pictures, all of which were taken on the same day. It must be very rare, since I was not able to later replicate the problem. In 2015, Leica confirmed that the green artifacts are from a known readout error that may only rarely occur if part of an image is saturated. It is worth noting that the green stripes have not as yet happened with the new sensor, though there has occasionally been a green cast in strong highlight areas.

The sun is the most common object that causes strong saturation in a small part of the image. As when using any rangefinder camera having a focal plane shutter, great care is used when taking any picture toward the direction of the sun. Specifically, the camera is quickly panned over to the subject to take the picture, then quickly pointed back away from the subject. This limits time that the sun image can enter the camera to under a second or two.

Intermittent Green Stripes, but in Only a Few (1 in 1000) Leica M9 Images.

Green stripes with Leica M9, inadvertently imaged while testing some lenses for flare.

(Only happened with original sensor. Has not yet happened with replacement sensor.)

© Copyright 2013 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

| Horizontal green stripe in an image taken with the Leica M9, when an area on the left edge of the picture is saturated. It is with a 135mm f/4 Elmar lens, set to f/8. Exposure is 1/2000 sec. at f/8, Pull 80 ISO. The picture, taken to flare test the lens, revealed anomalies in the Leica M9. If the extreme left of the image is saturated, a green stripe extends from the left edge to the image midline, but not past the midline. This is the entire picture, not a crop. |

Here, we have a rare green block of pixels that appeared when the left side of the image was slightly more saturated. The exposure is 1/4000 sec. at f/8, Pull 80 ISO setting. The green area again extends to the midline of the picture, and stops suddenly. This leads one to wonder if the sensor might be two 18x24mm fields that are read out separately. Pictures taken just after this did not have such artifacts. On average, this occurs in less than 1 out of every 1,000 images.

|

Hot Pixels, Including Transient Hot Pixel Clusters

Somewhat important is that the Leica M9 camera has several "hot pixels", including some clusters of contiguous hot pixels larger than 2x2. After some observation, I found that two types of hot pixels are most dominant. (This section applies only to the original sensor, since the replacement sensor had no obvious hot pixel clusters and was not evaluated for hot pixels.)

The first and worst type of hot pixels are "always on", with most being red. These are more obvious in low light or at high ISO settings, but also appear in shadow areas of normal pictures. Fortunately, most of these are well away from the center. These are more obvious versus the ISO setting than hot pixels in any of my previous digital cameras (including my 12 year old Sony DSC-F707), so they often have to be digitally retouched out of pictures.

The second type of hot pixels are transient. This is not something I've experienced with any other camera. Some of these transient hot pixels are clusters of hot pixels as large as 4x4 pixels (16 contiguous hot pixels!), with the brightest of these being red, but which are surrounded by even more hot pixels, specifically, up to 30 dimmer pixels having various shades of green and blue, most of which have been observed to be on the right side of the red pixels. It usually takes processing to see the dimmer green and blue pixels, but the brighter red clusters are obvious. These hot pixel clusters appear even at low ISO settings, including the pull 80 setting.

While the latter hot pixel clusters are transient, they often appear in the same locations. The interesting difference in the Leica M9 transient hot pixels is that they seem to be most obvious only in the first picture or two that I take after the camera has not been used for at least a few hours. If I take a series of pictures, the brightness of the transient hot pixels seems to be reduced with each picture. It is almost as if something was causing small areas on the CCD to slowly build up a charge as time goes by between pictures, but that the charge (if this is the cause) is reduced when taking a series of pictures. Large clusters of hot pixels seem unusual, even when most are transient.

When both types of hot pixel cluster are considered, there are seven relatively obvious ones (5 major, 1 moderate, 1 minor). The column and row coordinates are shown below, counting from the upper left corner. These are followed by the brightness, expressed as the DN number in an 8 bit image:

* Coordinates: 2134 / 2622 (109 DN red for 8 bit image, when BG is 40 DN)

* Coordinates: 2484 / 2570 (99 DN red, when BG is 1 DN)

* Coordinates: 2716 / 1762 (159 DN red-wht, 3 pixel spike by sat. area; only in img. 4850)

* Coordinates: 3386 / 852 (102 DN red)

* Coordinates: 3610 / 331 (single hot pixel; 125 DN white)

* Coordinates: 3838 / 549 (dimmer gray hot pixel: 47 DN)

* Coordinates: 3846 / 1730 (brightest pixel in cluster is 154 DN)

* Coordinates: 5056 / 1512 (single hot pixel; 107 DN blue)

Notes: Some hot pixel clusters are obvious even if the background is not a very dark.

Transient Hot Pixel Clusters in the Leica M9.

Transient hot pixel clusters in original the Leica M9 image sensor. These are most dominant in the first picture taken after the camera has not been used for at least a few hours.

© Copyright 2013, 2016 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

| One of several hot pixel clusters in this Leica M9 is at the bottom center of this unprocessed 100 percent crop. It is from a picture of the crescent moon setting, in the astrophotography section below. The exposure is 1/4 sec. at ISO 80. The brightest red pixels form a contiguous 4x3 cluster. The brightest of these has an 8-bit DN of 67, with the background being 0. This transient effect is most evident in the first picture taken after the camera has been unused a few hours. |

This 400 percent crop has been processed to show dimmer pixels around the main cluster of red pixels. Many dimmer red, green, or blue pixels surround the brighter 4x3 cluster, but these are so dim (1 to 8 DN) that they can't even be seen without considerable image processing. The brightest red pixels appear closer to white in this enhanced enlargement. Pixel clusters like these were only obvious in the first picture or two I took in the moon set series.

|

Image Sensor Cover Glass Coating Corrosion (a.k.a. Sensor Corrosion)

Sensor corrosion is an area where I thought that my Leica M9 might dodge the bullet, since the sensor had only been cleaned twice, both times by Leica. I had never attempted to clean the sensor myself. One theory of the time was that the sensor cover glass coating had to be breached in a small area for corrosion to begin (as opposed to corrosion starting spontaneously), so I thought my M9 might be safe from it.

However, I noticed some odd artifacts in early 2016, only weeks before the camera's extended warranty was to expire. The first sign was not actually dark spots, but was instead local blooming around highlights that only happened at certain sensor coordinates. (In other words, bright features rather than dark ones.)

The first artifact was small, but before long, multiple artifacts exceeding 20 pixels in width had been found. I prepared some sample photos and posted them so Leica could see them. Their people suspected the cause was indeed sensor corrosion, but they would need to see the camera to be sure.

Unfortunately, the number, size, and nature of the sensor defects make it impractical to process them out of most pictures. The sheer size of the artifacts means that they are obvious at almost all f-stops.

When the problem came to light, there was a backlog of parts at Leica, so the repair timing was going to cause my M9 to be in for service just when I had hoped to go on my first real vacation since about 2003. The purpose was to take photos with the M9 while I still had enough health to travel some distance in a given day. Fortunately, it looked like Leica may have had a temporary solution.

Image Sensor Cover Glass Coating Corrosion in Leica M9 (Early to Moderate Stages)

Early to moderate stages of sensor cover glass coating corrosion in the Leica M9.

© Copyright 2016 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

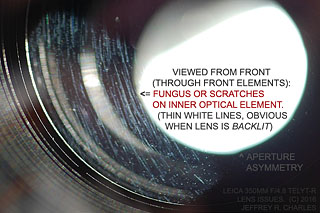

| Early stages of Leica M9 sensor cover glass coating corrosion were originally thought to be hot pixels, except that there was a curious dark spot in the center. Distortion on the right of this crescent moon image was one of the early signs. The bright vertical spike has a dark diagonal line through it. I had no idea what it was, and initially thought the dark area could be a distant contrail. There was no power line in the image to cause a diffraction spike. Unrelated "tearing" on the left of the crescent is from aliasing, as is the red and cyan fringing. This 150 percent crop is from a 1 sec. exposure at f/4.0 (ISO 160) with a 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit-M lens. Not bad for 90mm! |

This image shows a more advanced stage of sensor corrosion, with the defect exceeding 20 pixels in height. The greenish bulge on the right side of the glow around the bright part of the moon was first thought to be from the green stripe flaw (shown in two other pictures), but it was not in the right part of the sensor for that. Also, when the sensor defect was away from the moon, it looked like a dark structure with a bright ring around it. The far fainter (barely visible) inverted blue crescent that intersects the moon at the 1:30 position is a reflection from a filter. This 75 percent crop is a 2 sec. exposure at ISO 500 with a 180mm f/4 Telyt-R lens, set to f/4.8.

|

|

|

| Shadows of two sensor corrosion structures in an image of the sky. Just before this photo was taken, these spots and rings were found to be the culprit. As the limb of the rising moon crossed the right spot, it appeared to have a bright bulge on it, which disappeared as the moon cleared the spot and ring. At the time this was taken, there were at least 14 sensor defects of similar size. |

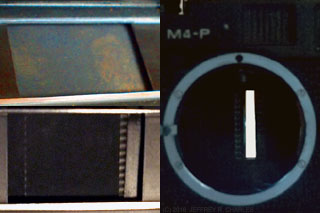

This image is flipped to match the orientation of the picture at left, and shows corrosion structures as seen from the front side of the sensor. The left spot even shows the surrounding ring. The right spot appears to have dim tracks leading away from it. The dark areas appear to have some structure, with most having two or more dark spots, as opposed to being single spots.

|

Other Quirks

The Leica M9 has exhibited only a few unexpected quirks other than the infinity focus issue. One is that has never recorded the estimated f/stop in the JPEG image EXIF data, even though the external meter cell has been shown to work based on its influence on the meter readout brightness. There is also a place just to the lower left of the rear LCD screen where the leatherette keeps trying to peel up. Minor, but something to keep an eye on in case the leatherette is brittle like the older vulcanite.

On one occasion, the camera, even though in singe shot mode, appeared to save images only to the buffer and never write them to the memory card. This may have been some sort of crash, because the camera later could not read from the card and its LCD screen didn't turn off when the power was turned off. Just before this started, the motor didn't advance after the last picture had been taken, even though the busy light was not on. The motor only advanced when the camera was switched off. The images remained visible on the camera screen even after turning the camera off and on, but the camera could not read the card later on.

When I read the card in my computer, none of the recent images were on it, so I lost all pictures I took during that situation, even though the camera had been powered on and off a few times and the battery changed when it was off. Fortunately, these were only test shots, so most were easily replicated. Everything including the memory card worked OK later. This gave me the impression the camera power switch may be a soft switch, similar to that on many computers.

There was one occasion when I found that a menu setting did not take when it was made immediately prior to the camera displaying a low battery warning. This only happened once, and this aspect of the camera worked fine when the battery was recharged.

In 2015, the camera did this again, but kept getting worse until it would not take pictures at all. Recovery required many steps that Leica recommended, including reset and re-installation of the firmware, but at least the camera did not have to be sent in (again) to address it. Unfortunately, Leica's hot pixel mapping may not have survived the process, since hot pixel clusters are now evident.

Everyday Pictures with the Leica M9

For anyone who has used a Leica M film camera, the Leica M9 should be relatively easy to use. In fact, I found it to be the easiest to use digital camera I ever encountered. If shooting at the base ISO and full resolution, there are often only four things to set: Shutter speed, aperture, focus, and white balance. Pretty much the same as using a Leica M film camera, except that you don't have to load film and you can select white balance instead of putting filters on the lens.

Personally, I find setting basic functions like the above to be easier than selecting from a myriad of program modes that vary from brand to brand in digital cameras. The Leica M9 menus are also relatively shallow, and the settings made most often are generally toward the top. It's simpler (at least for me) than even my Micro 4/3 camera. About the only thing I'd change is to add a dedicated white balance button and a small always on LCD (similar to that on the Epson R-D1) to show settings.

It sort of reminds me of the difference between PC and a Mac computers, back when DOS was all that most ran on a PC. If learning the processes required to use DOS had appeal, or if a PC it was the only affordable choice, it was appealing. If one instead wanted results without all the process, the Mac was the way to go, though it cost more. In the end, a Mac had less real cost (considering one's time), because it was possible, even easy, for many to get results with it.

In digital cameras, those who are into the process of learning a camera as much as obtaining the end product of taking pictures with it can dive into deep DSLR menus and set up stuff as long as they want. Those who are into the end product of getting good photos more than the process, can just use the Leica M9 and take pictures!

Even during the first week of use, I missed fewer pictures with the Leica M9 than I did with my Micro 4/3 camera. Even better, the clear rangefinder viewfinder provides a view of the subject at the very instant the picture is taken, so you quickly get a feel for whether or not you got the intended shot. The only thing that took a little getting used to was the 0.68x finder makes the subject look farther away than the 0.91x finder on the Leica M3. For people who are used to the M4-P and later Leica M film cameras, the difference between their 0.72x finders and the 0.68x M9 finder won't be as obvious.

Below are a few photos of everyday subjects, taken with the Leica M9. Landscapes are not included for now due to the apparent infinity focus issue, but some may be added after that is addressed under warranty.

Everyday Pictures with the Leica M9. (Pictures at infinity focus not added until 2015.)

Everyday Pictures with the Leica M9.

© Copyright 2013 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

Grab Shot of Utility Pole and Sky

When I went out the door one day, cloud formations behind a nearby power pole caught my eye, so I went back in the house, grabbed the M9, put on a 75mm lens and took this picture. The M9's fast power on time and simplicity of use made all the difference. By the time I took a second picture, the clouds had changed enough that the scene was no longer as interesting, but this first shot was what I wanted. The full size image holds up to even pixel peeping, being sharp as a tack and isolating the pole from the sky by virtue of high resolution on the pole. The original was taken with color saturation low, but it was possible to increase the saturation in post without noise becoming obvious like it would have in an image from my Micro 4/3 camera. A huge full frame digital SLR will easily take as good of a picture, but I doubt I would have gotten the shot in time with one.

|

|

|

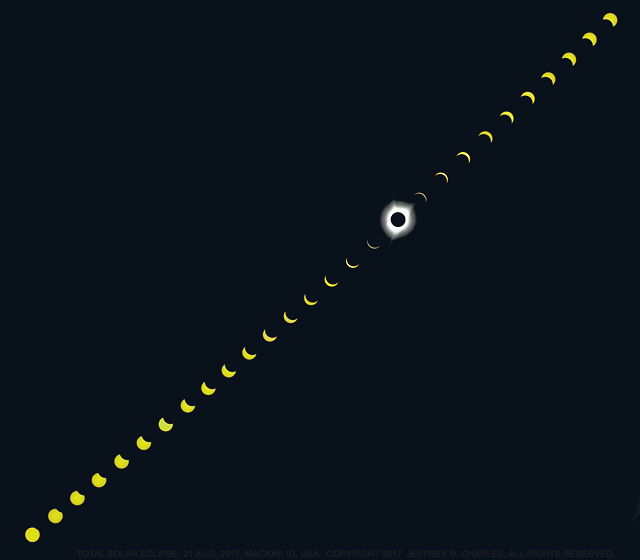

Mt. McCaleb from about 1 km northwest of Mackay, ID (haze from smoke processed out).

Mt McCaleb is an interesting mountain that has a different appearance, depending on location and lighting. Taken with a Leica M9 camera and 50mm f/1.4 Summilux-M ASPH lens. Exposure was 1/750 second at f/6.8, ISO 80. Tungsten white balance was used as an experiment to see if adding more blue to the original image would make it easier to process out strong haze from the smoke by removing the large amount of excess blue color from the original. It may have helped a little. Even the Leica M9 JPEG image had enough overhead to process out the strong haze that was caused by local smoke from forest fires. Copyright 2017 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

Smoke-Enhanced red sunset, from White Knob Motel, about 3km SE of Mackay, ID.

In 2017, sunsets were very colorful in the Mackay, ID area, due to lingering smoke from distant forest fires. The warm color is more obvious when clouds were present, but still interesting at other times. Leica M9 with 50mm f/1.4 Summilux-M ASPH. 1/45 at f/5.6, ISO 80. Brilliant color in images like this, taken at the "Pull 80" ISO setting, remind me of the color that Kodachrome slides used to capture. Copyright 2017 Jeffrey R. Charles. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|

Pepper Cat Looking at Me Instead of the Camera Lens

Manual focus with the Leica M9 rangefinder is about as fast as manual focus with my Micro 4/3 camera and its EVF, so I rarely miss cat shots while fiddling with the camera. The M9 also has less noise at ISO 800 than my Micro 4/3 camera does at 400. There is one difference though. My cat makes eye contact more than most cats, and since she can see part of my face on one side of the M9 camera, she looks at me instead of the lens. (All cats probably won't do this, but she does.) This is why she's looking a little to the left. Fortunately, I was later able to keep her from doing this as much by using my left eye to focus. This actually shows one of the strengths of the Leica rangefinder. Since its eyepiece is in an upper corner, using the camera is not like putting a veil over your face, which lets you stay better connected with your subject. For portraits, a person will respond to a suggestion that they look at the lens, even if a cat won't.

|

|

|

Pepper Cat Surveying The Great Outdoors, with Her Reflections Looking Back

Reflections on a Pepper Cat. This is Pepper cat and her reflections, captured with a 90mm Tele-Elmarit-M Type II lens, working at about f/3.1. This lens provides enough working distance that Pepper wasn't distracted by me or the camera. One curious but good thing is that turning on the Leica M9 does not seem to distract the cat, while turning on my Micro 4/3 camera, even from 20 feet away, will get her attention or even wake her up. It might be some high frequency sound that the MFT camera makes, but that the Leica M9 does not exhibit. For now (prior to warranty service), when wider apertures are used at close distances, I have to focus the rangefinder, then lean forward 2 or 3 cm in order for the image to have the same focus I set in the rangefinder. This could in part be related to the rangefinder showing infinity focus when each lens is set to infinity, while actual photos don't quite reach infinity focus. Best focus in the image is a bit closer than the rangefinder indicates, at all distances and with all lenses. This was fixed by Leica in 2015.

|

|

|

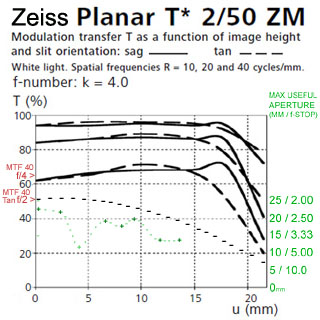

Pepper Cat Enjoying the Highest Indoor Vantage Point